Fishing for Gems.

The first, un-skippable step I would recommend to any artist, no matter where they are in their career.

When I was a young musician, people would ask me what I wanted for my work in the world. I would shrug and say things like, “I want us to be the best band in the world,” or “I just want to do it and keep getting better,” and “I’d like to make a living as an artist.” And while there’s nothing wrong with these answers, the fact was I didn’t quite understand the values underpinning these desires, and that made it tricky to know what I needed when it came time to tackling big decisions.

For example, what did it mean to be the best band in the world? Did I mean commercially, irrefutably, number-1 around-the-world-best? Number-1 for weeks on end-best? Did I mean critically acclaimed, or culturally-beloved-best? Or always striving for the next creative milestone-best? I could have been valuing any number of things with these statements: mastery, quality, grit, artistry. But most likely I was placing a high value on money, power and prestige.

“I just want to do it and keep getting better,” was my way of saying I valued prolific artistry (the opposite of perfectionism), longevity and transformation. And making a living was about a certain level of dependability, freedom, and independence, which was really important to me, and grated against our signing to a major label.

This post is part of the Artist’s Almanac section of Izzi Club, free to all subscribers until April 2025. Subscribers can opt out of this section at any time.

The Preatures at St Kilda Fest, Melbourne, 2019.

As I write this, my husband Rupert is pacing our living room floor, making I’m frustrated please drop what you’re doing and talk to me noises.

He’s a few months deep into founding his own startup here in San Francisco - a company called Unternet. In a nutshell: he’s trying to save the internet from en-shitification. Good luck Rups! Last year he had a round of successful pre-seed funding and now he’s in the weeds of actually running a company: employing people, taking meetings with new investors, figuring out who to bring on to do his accounting, tax, design, engineering, operations, the list goes on. You know, all the shit that has nothing to do with the thing you are passionate about putting into the world but nevertheless must happen and happen well.

Rups is agitated because the new operations person he’s been excited about bringing on board has emailed him with a list of questions about the company; its vision, culture, what defines it, that sorta thing. “I don’t have time for this,” he says to me, beginning to make toast. “I just need someone who can jump right in and get to work.” He licks butter off his fingers and looks at me, and I totally get it. It feels counterintuitive to sit and fill out questionnaires and think about the big picture when there’s momentum and a million other things to get to. And frankly, as ‘the artist’ in the visionary role, it can be an annoying point of friction to have to explain yourself and your work. To pin it down feels like catching a cloud mid-air.

There are many good reasons why we resist defining ourselves and our work, especially in the early stages of an idea. I would say that protecting your right to evolve and surprise - even morph entirely - is the number one requirement of surviving as an artist, and the emphasis we have now on the ironically homogenous and cumbersome personal brand is the antithesis of this and so vomit I can’t even with it. But I bring up Rups’ situation because I see parallels in the way the startup world mirrors the signing of acts to labels, with some obvious differences that I’ll talk about another time. For right now I’m looking at it through the lens of my own experience with the band: there’s something people are excited about, an upswell of momentum, hype, investment, and expectation. In the startup world though, there is emphasis on culture building at the outset. I tell Rups that as annoying as it is, he can’t skip this step. I tell him he must hire OpsGuy, my new favourite person (he does). And I tell him I wish I’d had someone like that sit me down in 2013 amidst the crazy clamouring of a band on the brink of success and ask some basic questions like, what is really important to you?

In 2020 my friend and mentor Rachael shared a values exercise with me and I loved it so much I tried it on friends and ended up expanding on it and calling it Fishing for Gems1. Instead of thinking about what your values are, Fishing for Gems draws them out like jewels bubbling up from the deep. With all the artists I’ve mentored over the years, I always begin our time together with this exercise. It’s cool to see them go from puzzlement and slight annoyance at the repetition, to opening up in wonder as the process unfolds.

I often warn my mentees that in doing this exercise, some proverbial walls may collapse. But ultimately, no matter what stage of your career you’re at, experience will draw some version of this process out of you whether you like it or not.

In classic stories there’s often a quest for a magical item like a chalice, gemstone or piece of gold hidden in a temple or guarded by a dragon. Once the hero finds the treasure and claims it, whether through stealth or cunning or strength, the cave, temple or even the ground beneath them begins to crumble and self-destruct. They have to make a quick escape.

Fishing for Gems is a series of questions like the ones I’ve listed below. There are about 10 questions all up, some I’ll talk about in later posts. I ask my mentees to write them out with pen and paper in a large A6 sketchpad. Do not use a computer or device. This is about being truthful about who they are and what they do, and it’s too easy to self-edit on a keypad. Be specific, I tell them. If you like reading gossip mags and smoking ciggies in the bath, put it down.

How do you fill your personal and creative space? What kind of objects, textures, colours and smells are present? What’s the atmosphere like? List as many things as you want.

How do you spend your time?

What do you devote your energy to?

How and on what do you spend your money?

When in conversation with others, what topics light you up the most?

From the answers they compile, we begin to draw out threads of things that group together and overlap and what they may represent. For example, if they have a living or work space filled with candles, incense, and flowers, question what it is about those items that they appreciate? Is it ritual? Or maybe it’s quality, beauty, or even scent (sensuality)? If they collect books about punk rock or some niche artistic movement, what is it in them that they align with? Artistry, irreverence, rebellion? Or maybe they devote their energy to moving around from place-to-place? What’s that about? In sessions I have spent sometimes hours with artists drawing maps and experimenting with different words until we arrive at what feels right. Words have flavours and associations that are unique to everyone so finding the right word for a value is important. The more I’ve done this exercise myself, the more refined the distillations become.

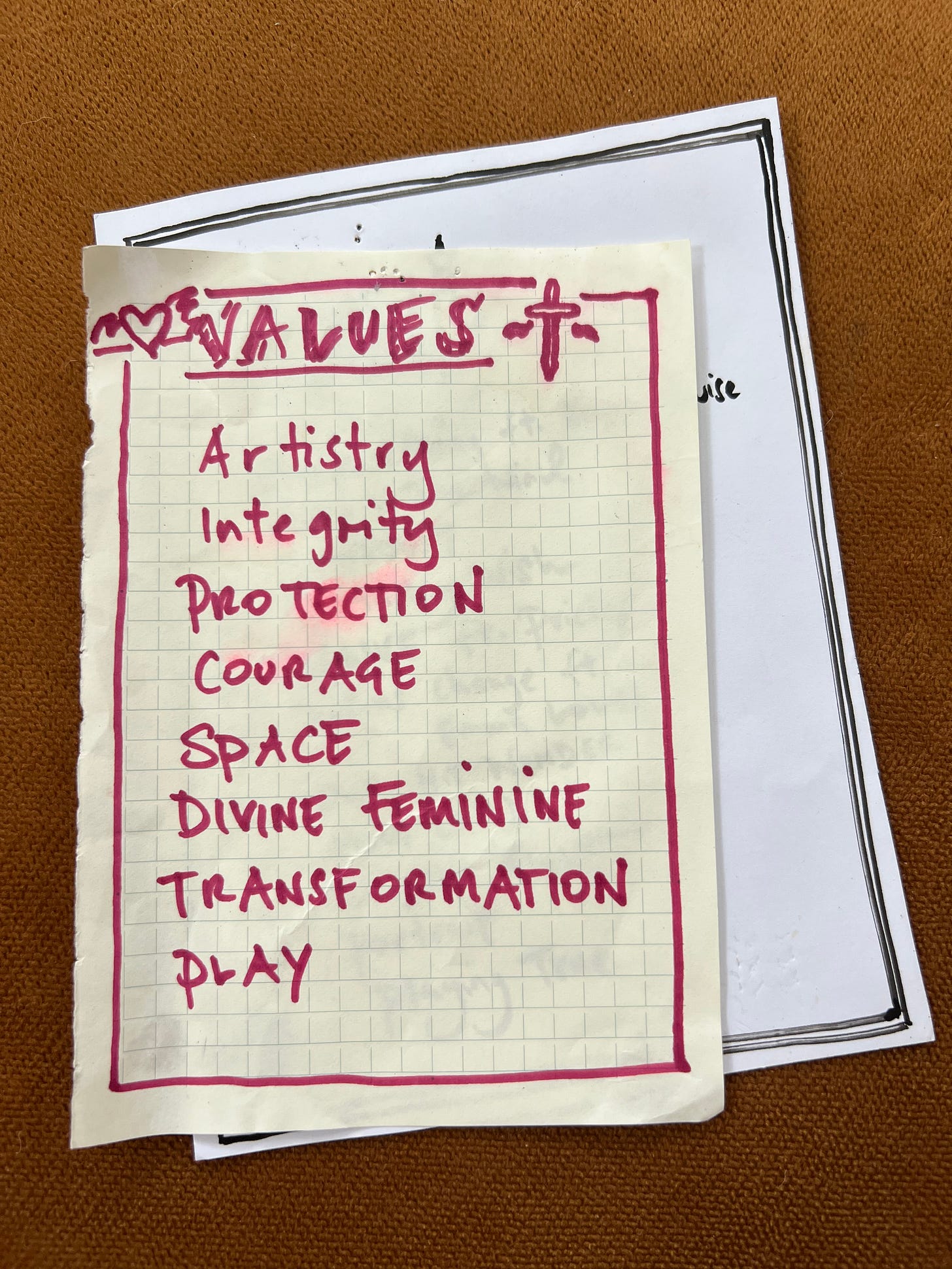

Here was my list in 2020. Doing it with a friend and glass of wine is pretty bloody good.

izzi x

This post is part of the Artist’s Almanac section of Izzi Club, free to all subscribers until April 2025. To opt out of this section, go to your account settings, navigate to izzi club, and then toggle off the notifications for The Artist’s Almanac. A gray toggle indicates you've opted out of that section.

I called it Mining for Gems for a while but that felt a bit too extraction-like. The fishing metaphor has a more easeful, Lynchian feel to it.

Rupert needs to do this. It’s like a trip to the dentist or going to get vaccinated. These things are scary at first but if you can point out the long-term benefits and lead by example, people will get on board. Those that don’t will fall by the wayside. If he wants to bring the best, like-minded people with him he needs to explore what it is that he wants to do and be able to articulate it. It’s called “LEADERSHIP”. It will also form the basis of who he hires as well as where the project goes. Certainly these goals and aspirations may change over time. Nimbleness is an important part of the program. But if you can do it as problem solving and are open and transparent about it with the team then everyone wins.